The History of Charlotte

Whether you’re a visitor, a proud native or an enthusiastic transplant who calls Charlotte home, you’re not “official” until you’ve become well-versed on some of the lesser-known ins and outs of the Queen City’s story.

by Tom Hanchett

Have you ever wondered why Charlotte defies most other cities by calling downtown “Uptown”? Why the NBA team’s mascot is an angry hornet? Or why you’ll see a crown on so much of the city’s insignia?

Charlotte may look like a brand-new city, but there’s a rich history at every turn. Its roots run deep in the Old South, way back before the American Revolution. As the New South dawned after the Civil War, Charlotte took off – first as a railroad junction and then as a cotton mill hub. During the Civil Rights era, Charlotte took part in integration efforts through organized sit-ins by Johnson C. Smith University students and intentional actions taken by a former mayor.

Today, Charlotte is one of America’s largest banking centers and one of the nation’s fastest-growing metropolitan areas. Newcomers roll in daily from across the United States and around the globe.

There’s a sense of possibility and of change. Charlotte is a place that asks you to dig in, to find connections and to make history here yourself.

Charlotte in the Old South

From its Colonial inception to its part in the U.S.’s first gold rush, the city of Charlotte has made a name for herself in contributions to the nation’s history.

The Queen City

Charlotte calls itself the Queen City. But why? The nickname offers a hint that this community is older than the U.S.

King George III still ruled the Colonies when European settlers chartered the town back in 1768. They named the new hamlet after the King’s wife, Queen Charlotte, and gave the surrounding county the name Mecklenburg in honor of her majesty’s birthplace in Germany.

The Creation of Uptown

If you look at a map of Center City Charlotte today, you’ll still see the grid of square blocks that points to its time under Colonial influence. Tryon, the city’s main street, still carries the name of North Carolina’s Colonial governor William Tryon.

Interestingly enough, Tryon Street does not align to the compass, as in many Colonial towns. Instead of running strictly north-south, it follows a natural ridgeline. That’s because it predates European settlement. Tyron Street follows the Nations Path, the great trading route of the Catawba and other Native American tribes, which ran from Georgia up to the Chesapeake Bay. Today’s Interstate 85 traces that same route.

The Tryon Street ridgeline is the reason behind Charlotte’s custom of calling its downtown “Uptown.” Head to Independence Square at the heart of the Center City; no matter which way you approach it, you’ll be moving gently upward.

Mecklenburg Resolves

Independence Square got its name during the American Revolution. In May of 1775, more than a year before Patriot leaders signed the Declaration of Independence, Charlotte made its own statement of defiance against Britain. The Mecklenburg Resolves of May 31, 1775, declared the “authority of the King or Parliament” to be “null and void.”

Tradition holds that there was even a full-blown Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence created on May 20, 1775. However, no copies exist, and the document never appeared in any Colonial newspapers or other records. Although there isn’t physical proof of its existence, it’s city tradition to celebrate the Meck Dec each year on May 20.

In June 1775, a local tavern-keeper named James Jack served as a messenger carrying important papers to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The documents could have been the Resolves or the “Meck Dec,” but it’s unclear. In Jack’s honor, locals and visitors can admire a statue of him on horseback galloping along Little Sugar Creek Greenway, just east of Uptown.

Hornets’ Nest of Rebellion

Late in the Revolution, British General Cornwallis swept into town – and soon wished he hadn’t. Local sharpshooters peppered his men mercilessly in the 1780 Battle of Charlotte and the Battle of Kings Mountain nearby, now the site of the Kings Mountain National and State Parks at the foot of the Crowders Mountain ridgeline.

As he departed, it is said that Cornwallis wrote in his diary that Charlotte was a “hornet’s nest of rebellion.” Today, the hornet and hornet’s nest are popular civic symbols. You will find them on police officers’ uniforms and NBA Charlotte Hornets’ uniforms, among other places in town.

The First U.S. Gold Rush

After the Revolution, a totally unexpected event put Charlotte on the money map. In 1799, a boy named Conrad Reed, playing in a creek 25 miles east of the city, picked up a 17-pound rock that glittered. His parents used it for a doorstop until a sharp-eyed merchant offered them $3.50 cash for it. It was the first piece of gold ever discovered in North America.

By 1837, so much gold was coming out of the ground in the Charlotte vicinity that the U.S. built a branch Mint here. Things slowed after the 1849 California Gold Rush and in 1933 the building on Mint Street was about to be demolished. A group of citizens succeeded in getting it carefully dismantled, then reconstructed on Randolph Road, where it opened in 1936 as the Mint Museum, North Carolina’s first publicly funded museum of art.

Meanwhile, old mine shafts still lurk beneath Uptown. Head out to Reed Gold Mine near Albemarle, North Carolina, to explore the Reed family’s actual mineshafts and pan for gold yourself.

The Rise of Railroads

Though Charlotte’s gold history is romantic, railroads actually had a greater impact on the local economy. In 1852, local investors in Charlotte and upstate South Carolina succeeded at completing the first rail line to enter the heart of the Carolinas. It connected Charlotte with Columbia, South Carolina, where existing tracks transported goods to the port of Charleston, South Carolina. The North Carolina state legislature immediately authorized construction of a second line to link Charlotte with Raleigh, North Carolina.

That railroad crossroads made tiny Charlotte a hot spot in the Civil War from 1861 to 1865. The Confederates manufactured cannon and ironwork for their ships here, and when Richmond, Virginia, fell in the last days of battle, Confederate President Jefferson Davis fled south along the rail lines, holding a final full meeting of his cabinet in a house on Tryon Street.

New South Reinventions

Contributions to mining and the textile industry laid the framework for an evolution towards its future as a major U.S. banking hub and hub for higher education.

From Fields to Factories

Though the hardships of war touched most families, Charlotte came out of the Civil War stronger than ever. Troops had cut the railroad to Columbia, but it was quickly restored. African Americans, who comprised 40% of Mecklenburg population, were now free. Charlotte’s population doubled during the 1860s, hitting 4,473 in 1870.

Leaders in Charlotte and across the post-war South talked avidly of creating a New South. The region would no longer rely on slavery and farming; like the North, it would embrace factories and urbanization. Charlotte has gone through many waves of change from then to now, but that New South love of reinvention still defines the city’s spirit.

Textile Times

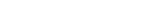

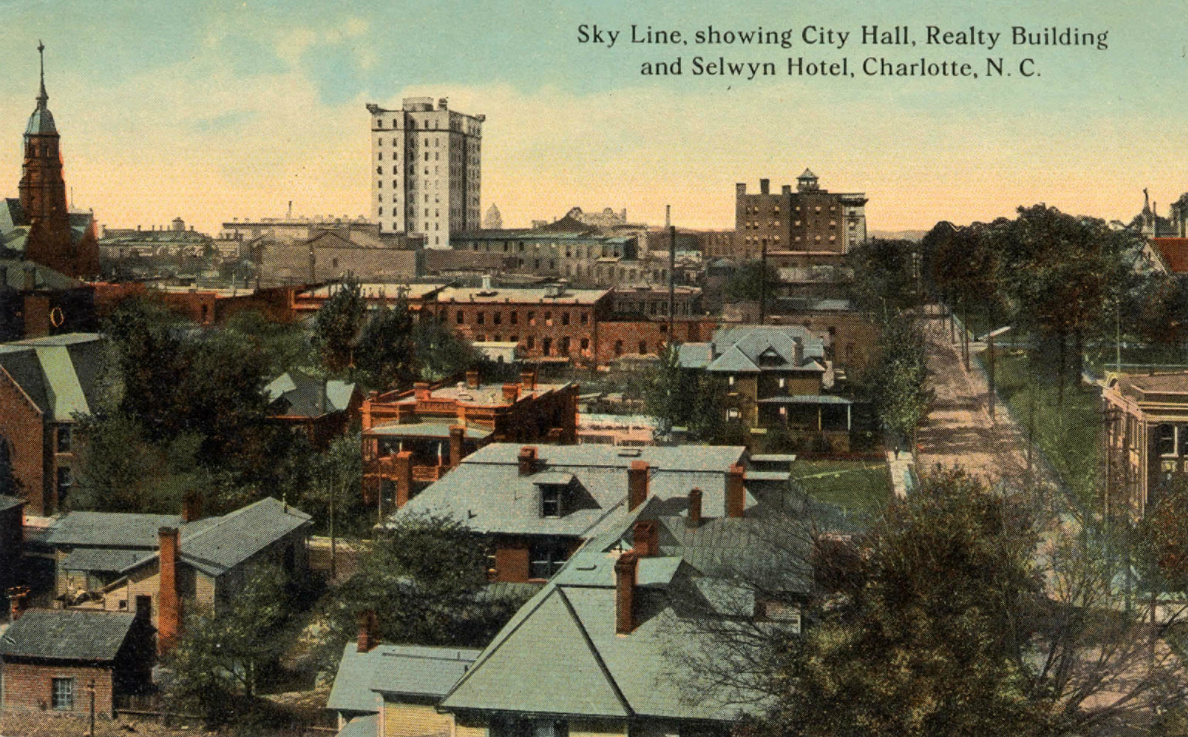

By the 1880s, Charlotte sat astride the Southern Railway mainline (the “main street of the South”) from Atlanta, Georgia, to Washington, D.C. Farmers from miles around brought cotton to the railroad platform Uptown Local promoters began building textile factories, starting with the 1881 Charlotte Cotton Mill that still stands at Graham and Fifth streets.

By the 1920s, this part of the Carolinas – from Greenville and Spartanburg in South Carolina to Winston-Salem and Durham in North Carolina – surpassed New England to become the nation’s top cotton manufacturing district. Charlotte blossomed as the trading city for the region. The city’s population soared from less than 20,000 residents at the turn of the century to more than 100,000 by 1940.

You can see textile history today at Optimist Hall, an 1892 cotton mill at the edge of Uptown that now bustles with more than 20 eateries. A mile further out via the LNYX Blue Line light rail, explore Charlotte’s NoDa neighborhood. It’s a cluster of former mill villages reborn as an eclectic arts district filled with pedestrian-friendly retail, nightlife, dining and music venues. Or look further to the now-suburban towns of Pineville, Cornelius, Kannapolis, Belmont, Mount Holly and Gastonia, where big brick mill buildings have been reimagined into restaurants, entertainment hubs, businesses and shops.

Cotton’s legacy lies behind other landscapes as well. The glass-roofed 1915 Latta Arcade and adjoining Brevard Court in Uptown – where employees of Uptown businesses now flock to restaurants and retail during the lunch hour – housed offices of cotton brokers. Myers Park, with its gracious greenways and curving, oak-shaded streets added by renowned Boston, Massachusetts, landscape planner John Nolen, was laid out in the 1910s for mill owners, bankers and utility executives. And Lake Wylie in South Carolina began as a hydroelectric project of James Buchanan Duke, who sold power to textile companies. You’ll recognize the name in Duke Energy, one of the largest electric power companies in the U.S., which is headquartered in Charlotte. Duke’s residence in Myers Park is now The Duke Mansion, a historic landmark that also serves as a popular bed-and-breakfast and event venue.

Hot-spot for National Brands

Charlotte was never a one-industry town; its central location made it the Carolinas’ sales and distribution hub for all kinds of goods. The Belk family built the South’s premier department store chain; Belk’s flagship store is in Charlotte. On Central Avenue, Leon Levine opened the first Family Dollar discount store, which now operates nationwide. Across the street, W.T. Harris operated a food market that blossomed into the regional grocer Harris Teeter. Charlotte salesman Philip L. Lance turned a raw peanuts deal gone awry into the ever-popular Lance crackers (now Snyder’s-Lance) brand. And nearby, a hometown hardware store grew into mega retailer now known as Lowe’s, headquartered today in Mooresville. Still other locally born brands, including Cheerwine and Bojangles’ Famous Chicken n’ Biscuits, also came to regional prominence thanks to Charlotte-area entrepreneurs.

Henry Ford chose Charlotte for a sprawling facility that assembled and distributed his famed Model T and Model A automobiles. The U.S. later used it to make Hercules missiles for the Cold War. Today it is Camp North End, an innovation incubator with hip office space, fledgling entrepreneurs (including the Leah & Louise restaurant of Subrina and Greg Collier, nominated for the James Beard award), and a schedule of outdoor events that draw happy crowds.

Campus Life

New South prosperity aided educational opportunities. Johnson C. Smith University (JCSU) was founded just west of Uptown immediately following the Civil War to educate “preachers and teachers,” leaders for the newly freed African American population.

In Myers Park, Queens College (now Queens University of Charlotte), also started by Presbyterians, was established as a school to educate young white women. The college opened in Uptown in 1857 as the Charlotte Female Institute (then the Seminary for Girls followed by Presbyterian Female College) before moving to the current Myers Park location in 1912. The college began the process of admitted men in the 1940s, becoming fully co-ed by 1987. The college made the decision to integrate in 1962, with the first Black student being admitted in 1963.

North of the city, elite Davidson College opened its doors in 1837 to provide liberal arts training to young white men. In 1961, trustees voted to accept African students with the admittance of a student from the Congo in 1962 and a second Congolese student inn 1963. In 1964, the college began admitting African American students. In 1969, women students from other colleges began taking “exchange classes,” with the school becoming fully co-ed in the fall of 1973.

These specialized colleges were joined by what is now the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, launched by Bonnie Cone in 1946. The campus serves more than 30,000 students annually today as one of North Carolina’s major research universities.

A Music Mecca

Colleges possessed no monopoly on culture. WBT, the first radio station licensed in the South, attracted a remarkable array of country music and gospel performers who sang live over the airwaves. RCA Victor and other record companies visited often. A South Tryon Street sidewalk plaque marks where Bill Monroe, the father of bluegrass music, cut his first discs in 1936. During the late 1930s, more records were made here than in Nashville, Tennessee.

The Newest New South

Through the actions of its citizens, the Queen City took its place on the national stage as a proponent for civil rights and equality.

Civil Rights Reform

Charlotte’s pace of reinvention began to accelerate in the late 20th century. A city that had once been a backcountry farm community before the Civil War and a regional textile center in the early decades of the New South now started to take a place on the national stage.

The new era began with the Civil Rights movement. The city’s African American leaders succeeded in desegregating Revolution Park and the city’s new airport in the mid-1950s. In 1960, students at JCSU organized one of the largest sit-in efforts in the South. Their demonstrations led to the opening of lunch counters to all.

But upscale restaurants still barred African Americans – until a remarkable series of events unfolded in May of 1963. Crusading dentist Dr. Reginald Hawkins led a march from JCSU to City Hall demanding total desegregation. Cities elsewhere in the South were meeting such requests with police dogs and firehoses. Then-mayor Stan Brookshire determined that Charlotte would be different. He phoned Chamber of Commerce leaders and quietly arranged for white-Black pairs to eat lunch, integrating each restaurant. The action – coming a year before the 1964 Civil Rights Act which required integration in all public places – gained national notice for Charlotte.

In an era when national businesses were looking to expand south, a welcoming image paid dividends. Charlotte’s progressive reputation solidified when the city became the U.S. test case for court-ordered busing to integrate schools in 1971 and again when Harvey Gantt won election as the first African American mayor of a large majority-white U.S. city in 1983. Between the early 1960s and early 1980s, Charlotte’s population grew by more than 50%.

A Banking Empire

Banking became Charlotte’s next frontier of change. The city already had robust local banks, thanks to a North Carolina law that allowed branches statewide. In 1982, banker Hugh McColl at North Carolina National Bank (NCNB) figured out how to buy a small out-of-state bank. The innovation sparked a massive rewriting of banking laws across the nation.

NCNB (rebranded as NationsBank) and local rival First Union (later renamed Wachovia, then bought by San Francisco, California-based Wells Fargo) rode the crest of the interstate banking wave, rapidly building two of America’s largest financial institutions. In 1998, McColl purchased San Francisco’s venerable giant Bank of America and moved the headquarters to the Queen City, creating the U.S.’s first coast-to-coast bank. Charlotte suddenly ranked second only to New York City as the nation’s biggest banking town.

A new skyline sprang into being along Tryon Street, the heart of Uptown. Or should it be called downtown? Longtime merchants insisted it had always been Uptown, and in a Sept. 23, 1974, resolution, City Council officially declared it so. A few years later, local leaders again chose a history-savvy name for another area being transformed by new construction. When Charlotte Douglas International Airport’s new terminal opened in 1982, the expressway linking it to Interstates 77 and 85 honored Charlotte-born Billy Graham, farm boy-turned global evangelist.

A Sports Stronghold

As Charlotte broke into the ranks of top-20 U.S. cities, major league sports arrived. In 1988, the beloved Charlotte Hornets brought professional basketball to a region known for its love of college hoops (thanks especially to North Carolina’s famed Duke University and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill rivalry, as well as Michael Jordan’s Tar Heel State roots). The Carolina Panthers NFL football team debuted in 1993. When David Tepper purchased the franchise in 2018, he added Charlotte FC, a Major League Soccer team that quickly developed a fervent fan base. The Charlotte Knights minor league baseball team also started in 1993, moving from a smaller stadium in Rock Hill, South Carolina, to newly built Truist Field in Uptown in 2014.

In auto racing, Charlotte had long been in the big league, ever since NASCAR ran its first-ever professional stock car race at a local dirt track in 1949. But now, as the sport became increasingly sophisticated, the high-tech engineering operations of most race teams clustered near mammoth Charlotte Motor Speedway. In 2010, the NASCAR Hall of Fame opened in a glistening Uptown building designed by Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, the internationally renowned firm that is also responsible for designing the Grand Louvre in Paris, France and other famous buildings across the world.

The NASCAR Hall of Fame is located in a district of Uptown known as Brooklyn. In the deepest period of racial segregation from the 1900s to the 1960s, Brooklyn functioned as a Black “city-within-the- city.” The federal Urban Renewal program bulldozed Brooklyn during the 1960s, involuntarily displacing over 1,000 households. Today, Charlotte officials are working with business and community leaders to re-invent part of the long-under-used Urban Renewal lands as Brooklyn Village, with a mix of offices, retail and housing – including affordable units. The Brooklyn Collective, a group of artists in the historic MIC Building on Brevard Street, strives to make sure that Black history is not forgotten.

A Cultural Melting Pot

Between 1990 and 2015, Mecklenburg County’s population doubled, surpassing one million residents. Governments in the city, county and outlying towns, still technically separate but all facing the same challenges of rapid urbanization, worked together to construct new hospitals, schools, roads and Charlotte’s first modern-day light rail transit lines.

While most newcomers arrived from across the nation, a growing number came from around the globe. The influx took many longtime Charlotteans by surprise; earlier immigration had largely bypassed this part of the South. A Brookings Institution report named Charlotte a Latino “hyper-growth” city in the 1990s, ranking it fourth in the nation. A subsequent study by Neilsen ranked Charlotte the fastest-growing major Latino metropolis in the entire U.S. from 2000 to 2013.

But Latinos made up only about half of immigrants. Signs written in Vietnamese, Arabic and Spanish dotted older suburban corridors, including Central Avenue and South Boulevard, where many newcomers launched businesses. Foreign-born families did not cluster in distinct neighborhoods, though, as in the Chinatowns and Little Italys of older U.S. immigrant destinations. At the edge of suburban Matthews, North Carolina, for instance, you could find Grand Asia Market, Lucy’s Colombian Bakery, Enzo’s Italian Market and a Mexican buffet in a single shopping center, with a Russian-Turkish grocery and a Greek pizza/Iranian kabob restaurant nearby.

Today, a growing culinary scene flourishes around the city, nurturing family-owned and locally built businesses. It’s been helped by Johnson & Wales University, known for its culinary classes, which opened its large Uptown campus in 2004.

Charlotte Past, Present & Future

At Independence Square, in the heart of Uptown, four statues tower over Tryon and Trade streets. Each link Charlotte’s history with the present and future.

- An African American railroad worker stands for transportation. That now includes rails, interstate highways and one of the nation’s top-10 busiest airports.

- A woman and child in textile mill worker uniforms represent industry. Manufacturing and distribution account for a sizable part of today’s economy.

- A gold miner symbolizes commerce. Banking surely heads that category in present-day Charlotte.

- And the fourth statue? It is a mother holding a baby – aptly symbolizing the future. Each of the other statues is facing this statute, therefore looking toward the future.

What does the future hold for Charlotte? With growth comes challenges. How do we construct the infrastructure and institutions needed for the burgeoning population? How do we ensure that opportunity reaches all of us? How do we reinforce a spirit of community, a true sense of respect among the fast-growing array of natives and newcomers of every background?

As surely as when country families came off the farm to staff the New South cotton mills, as surely as when Civil Rights activists and local officials joined together to open restaurants and schools to all, Charlotte will work to meet the challenges.

For that, we will be the history-makers.