10 Black Charlotteans Who Have Transformed Our City’s History

Read about Black men and women whose courage shaped Charlotte, then and now.

by Jonathan McFadden

You’ve likely heard the names John Belk and Hugh McColl in conversations about Charlotte’s storied history. But what about lesser-known, but just-as-important, Black pioneers like Daniel Sanders and Harvey Boyd? Many notable Black Charlotteans shaped the Queen City as we know it, and we’re still benefiting from their contributions.

Daniel Sanders

Johnson C. Smith University’s first Black president

Johnson C. Smith University is praised for its prominent Black leadership, but it wasn’t always that way. In its earliest years, the college, then known as Biddle University, was led by White men. That changed in 1891 when Daniel Sanders, a former slave who became a pastor and public-school principal in Wilmington, arrived in Charlotte as the university’s first Black president. He kept that role for 17 years until his death.

Dorothy Counts-Scoggins

Integrated Charlotte public schools

On Sept. 4, 1957, Dorothy Counts-Scoggins was one of four Black students who integrated Charlotte’s public schools. As she entered Harding High, throngs of people who opposed integration hurled racial epithets, spit and rocks at her. Although her stay at Harding was short (four days), photos of her courageously walking into school rallied Black people nationwide to push officials to reinforce the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, which declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional.

Frederick Douglas Alexander, Sr.

Charlotte’s first Black city councilman since Reconstruction

A businessman and civil rights activist, Frederick D. Alexander was elected Charlotte’s first Black city councilman in the 20th century. (Before his 1965 election, a Black person hadn’t served on the dais since the 1890s.) After winning reelection several times, he was elected to the North Carolina Senate in 1974 and served there until his death in 1980. Before his foray in politics, Alexander was a nationally known civil rights figure, particularly after hate groups bombed his westside home.

Harvey Boyd

Maker of the Mecklenburg County seal

In 1964, Matthews’ Harvey Boyd was a 20-year-old designer in The Charlotte Observer’s ad department when he saw a solicitation for designs for an official Mecklenburg County seal. He threw his hat in the ring and created an iconic emblem that featured imagery from the county’s past, present and likely future. He won, and now that seal is emblazoned countywide. He still lives in Matthews today.

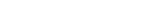

Harvey B. Gantt

Charlotte’s first Black mayor

Harvey Gantt made history when he was elected Charlotte’s first Black mayor in 1983, but it wasn’t his first time as a trailblazer. Twenty years earlier, he became the first Black student admitted to Clemson University. He would later co-found Gantt Huberman Architects in 1971 and join Charlotte City Council three years later. As mayor, he led Charlotte as it adopted its identity as a New South City. As an architect, he developed some of the city’s most recognizable landmarks, such as the Charlotte Transportation Center and Friendship Missionary Baptist Church. Today, he remains active in Charlotte’s political scene, serving on several business, civic and philanthropic boards.

Vi Lyles

First Black woman mayor of Charlotte

A former employee for the City of Charlotte, Vi Lyles was elected as Charlotte’s first Black female mayor in 2017 after having served as a city councilwoman for four years. Since then, she’s led the city through times both trying and triumphant. That includes strengthening the city’s connection with the corporate community to create more jobs, helping coordinate citywide response to the coronavirus and, most recently, signing a proclamation declaring racism a public health crisis.

Dr. Willie Griffin

Staff historian, Levine Museum of the New South

Raised in Charlotte’s Lincoln Heights neighborhood, Dr. Willie Griffin is the keeper of the city’s past, both the good and the bad. He formerly served as the assistant professor of African American history at The Citadel in Charleston, S.C., and holds a doctorate in U.S. history from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. A prolific civil rights scholar and educator, Dr. Griffin offers context that can enrich anyone’s understanding of where Charlotte’s been and where it could be headed next.

Glenn Burkins

Founder and publisher, Qcitymetro

In 2008, veteran journalist turned entrepreneur Glenn Burkins launched Qcitymetro, a digital news site for Charlotte’s Black readers. Along with The Charlotte Post, it chronicles the stories of Charlotte’s Black community with depth and nuance missing from most mainstream news outlets. A trusted and revered voice in Charlotte’s media scene, Burkins is a regular on WFAE’s Charlotte Talks Local News Roundup, a coveted business mentor and a sought-after moderator and facilitator.

Alvin C. Jacobs

Image activist

Alvin C. Jacobs Jr. travels the country documenting social justice movements, from Baltimore to Ferguson to New York to Charlotte. His photos from the 2016 protests after the shooting death of Keith Lamont Scott were featured prominently in the Levine Museum of the New South’s K(no)w Justice, K(no)w Peace exhibit. His Welcome to Brookhill exhibit at the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture documented the stories of neighbors living in an overlooked community on South Tryon Street. He’s been an artist-in-residence at the Gantt Center, a guest lecturer at Johnson C. Smith University and an in-demand photographer for the NFL, NBA and Jay-Z. His work has been so impactful that, in 2018, Charlotte Magazine named him the Charlottean of the Year.

Michael Jordan

Majority owner, the Charlotte Hornets

A North Carolina native, this former NBA superstar is the majority owner of the Charlotte Hornets and a community philanthropist. He’s used his platform more recently to vocally decry racial inequity, and he’s backed that talk with action by pledging $100 million over the next decade to organizations promoting social justice. Plus, his $7 million donation helped open the Novant Health Michael Jordan Family Medical Center to serve families in the city’s underserved communities.